Motivation

During breakfast this morning at the Homemade summer camp in 2004, I had the pleasure of meeting Miranda Moss. As we enjoyed our coffee, she shared details about her intriguing projects focused on “biodiversity of energy.” Miranda has already designed several PCBs (Printed Circuit Boards) aimed at harnessing solar energy. Currently, she is captivated by the potential of gravity batteries, which leverage mechanical principles to store and release energy.

Our conversation took an even more interesting turn when Fadri Pestalozzi (aka my husband) joined us. He introduced us to the concept of the Water Vortex Power Plant, sparking a lively discussion about sustainable energy solutions.

A gravitation water vortex plant in Austria - wikipedia source

Water Vortex Power Plant: An Overview

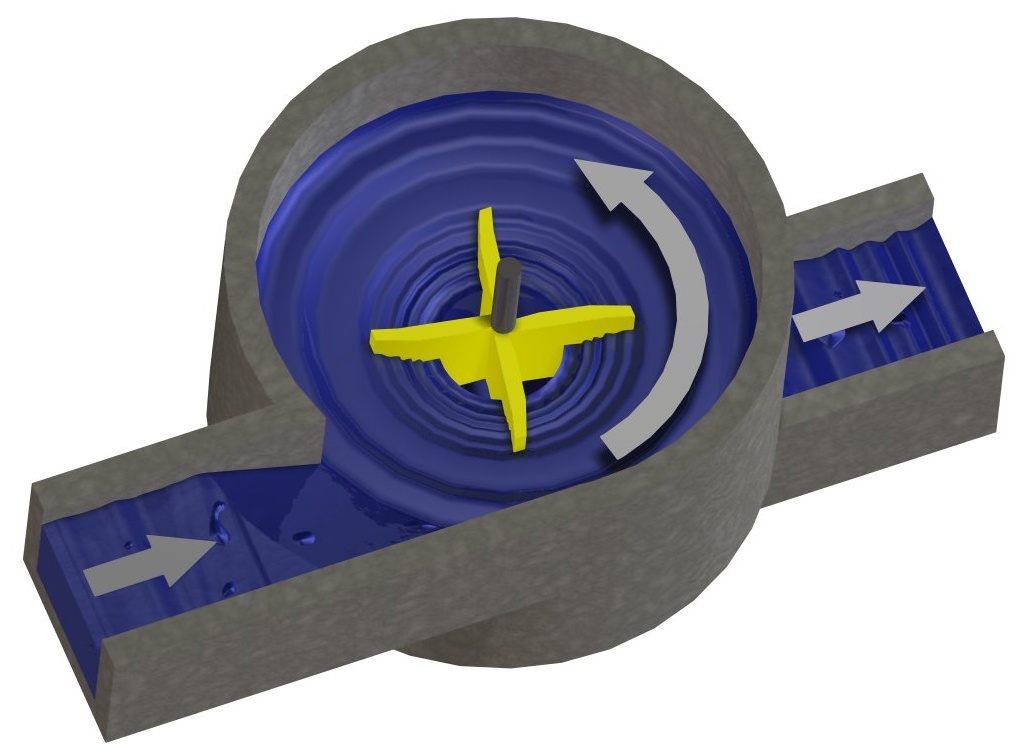

The Water Vortex Power Plant is an innovative approach to generating electricity by harnessing the natural motion of water. This technology utilizes the kinetic energy produced by a controlled water vortex to drive turbines and generate power. The history of this concept dates back to ancient techniques of water management and milling, but modern applications have optimized these principles for efficient energy production.

The primary purpose of a Water Vortex Power Plant is to provide a sustainable and environmentally friendly method of generating electricity. By utilizing the natural flow of water, it minimizes the ecological footprint compared to traditional hydroelectric power plants. This technology is particularly advantageous in areas with limited resources, as it can be implemented with relatively simple infrastructure and without the need for large-scale dams or reservoirs.

Hands-On Prototyping: The Initial Exploration

For our hands-on project, we started with the materials we had available, focusing initially on a NEMA 17 motor that I had brought along in my bag. To create a makeshift turbine, we designed a structure with blades to fit inside a plastic cup. We drilled holes into the cup and threaded a tube through it, using what was available to us in terms of tinkering materials. This included creative learning supplies such as scraps and items typically found at home.

Our first prototype utilized Lego pieces to build the motor’s structure atop the cup, which was intended to act as our turbine. We also incorporated wooden blocks from a stacking game and small hoses I had on hand, creating a rudimentary yet functional setup using tinkering techniques. This approach allowed us to rapidly iterate and adjust our design with readily available components.

Upon testing this initial prototype, we discovered a significant issue: the NEMA 17 motor required more torque to rotate the blades than our setup could provide. This realization prompted us to reconsider our design and the materials used. We concluded that for the next iteration, we would need a motor that could turn the shaft more easily and efficiently.

This process underscored the importance of prototyping and iterative design. By working hands-on with what we had, we were able to quickly identify limitations and gather insights for improving our approach. The collaborative environment and resourceful use of materials turned our challenges into learning opportunities, driving us toward a more viable solution for our energy generation project.

Hands-On Prototyping: The Second Exploration

For our second prototype, Miranda provided a motor with less friction on its shaft, which she had salvaged from a piece of discarded electronic equipment. This motor had a pulley firmly attached to its shaft, and we decided to utilize the pulley as it was rather than removing it.

One of the most interesting materials we used in this process was a wine cork. Cork, being easy to carve, allowed us to fit it onto the motor’s pulley securely. To ensure the cork stayed in place, we used hot glue to fix it firmly to the pulley.

We also took advantage of cork’s resilience to secure the new blades for our turbine. Unlike the first prototype, which used wooden blocks, we opted for PET bottles. The PET bottle served a dual purpose: it formed both the water tank to generate the vortex and the blades that the water would spin to drive the motor.

Additionally, the motor structure required an upgrade. Instead of using Lego pieces as in the first prototype, we employed metal L-brackets typically used in furniture assembly. These 90-degree angle brackets provided a more robust and stable framework for the motor.

This second prototype marked a significant improvement over the first, we managed to turn on the red LED! Through this iterative process, we learned the importance of material selection and adaptability. Each prototype taught us valuable lessons about the limitations and potential of our chosen components. This hands-on, collaborative tinkering approach allowed us to innovate creatively and make significant progress toward our goal of building a functional water vortex power plant.

Conclusion: Lessons Learned from the Prototyping Process

Throughout this hands-on prototyping journey, we learned that pursuing an idea with limited materials and resources is indeed possible. Even without access to advanced tools like 3D printers, laser cutters, or other materials typically found in our usual environment, we relied on the creativity and ingenuity of our team. The flexibility of materials and the collaborative effort allowed us to mentally stretch and innovate in the design of physical products.

Our experience with the quick, “dirty” prototyping process highlighted its primary advantage: it enables rapid proof-of-concept creation within a single day. By utilizing available materials such as electric components, hot glue, wood pieces, and metal structures, we could swiftly test our ideas. However, we also recognized the limitations of such prototypes. They serve as an initial testbed, helping us understand the design’s impact on efficiency and revealing areas for improvement.

One potential enhancement we identified is incorporating a gearbox to optimize the motor’s performance. Our goal was to generate enough energy to light a red LED, but the water vortex’s drag required higher speed and torque than our current setup could provide. A more refined vortex motor design, possibly created through 3D printing, could significantly improve efficiency.

from wikimedia commons

Additionally, the unique motor from discarded electronic posed documentation challenges for reproducibility. Despite this, the principles of collaborative and iterative design remained evident. While we could have spent more time on detailed calculations and designs, our one-day efforts demonstrated the power of hands-on experimentation.

Reflecting on the process, we see potential applications beyond this project. For instance, my mother’s rural small property with flowing water could benefit from this concept. Alternatively, the setup could serve as an intriguing artistic installation. Ultimately, this prototyping experience underscored the value of resourcefulness and teamwork in driving innovation and exploring new possibilities.

Our breakfast discussion highlights the essence of the summer camp: a collaborative, immersive environment where resourcefulness and shared knowledge drive innovation. Despite the limitations in materials and machinery, the camp’s focus on collective imagination and idea exchange fuels our creativity. It is within these constraints that we find the clarity and determination to push boundaries and explore new frontiers in sustainable technology.

More pictures and videos on Flickr Gallery

Lina Lopes

Lina Lopes

Tinkering for 2 Hours with a Canon EOS 40D That's Older Than My Daughter

Tinkering for 2 Hours with a Canon EOS 40D That's Older Than My Daughter